Birthright Citizenship

the case against it.

I have a perverse habit of listening to the New York Times “The Daily” podcast every morning while making breakfast, when I can stomach the topic. It’s my version of the Times crossword—trying to parse through what is being said, or not said, on the topic of the day. Occasionally I learn something about the subject, but most of the time I like to think I am learning about the collective mind of the sort of person who writes for and/or reads the New York Times.

This morning on The Daily, it was confidently asserted by one of the political correspondents that birthright citizenship is guaranteed by the US Constitution. This sort of thing is being asserted by many other regime outlets and ideologues today, and I thought it might be helpful to provide some sources to understand the case against this assertion.

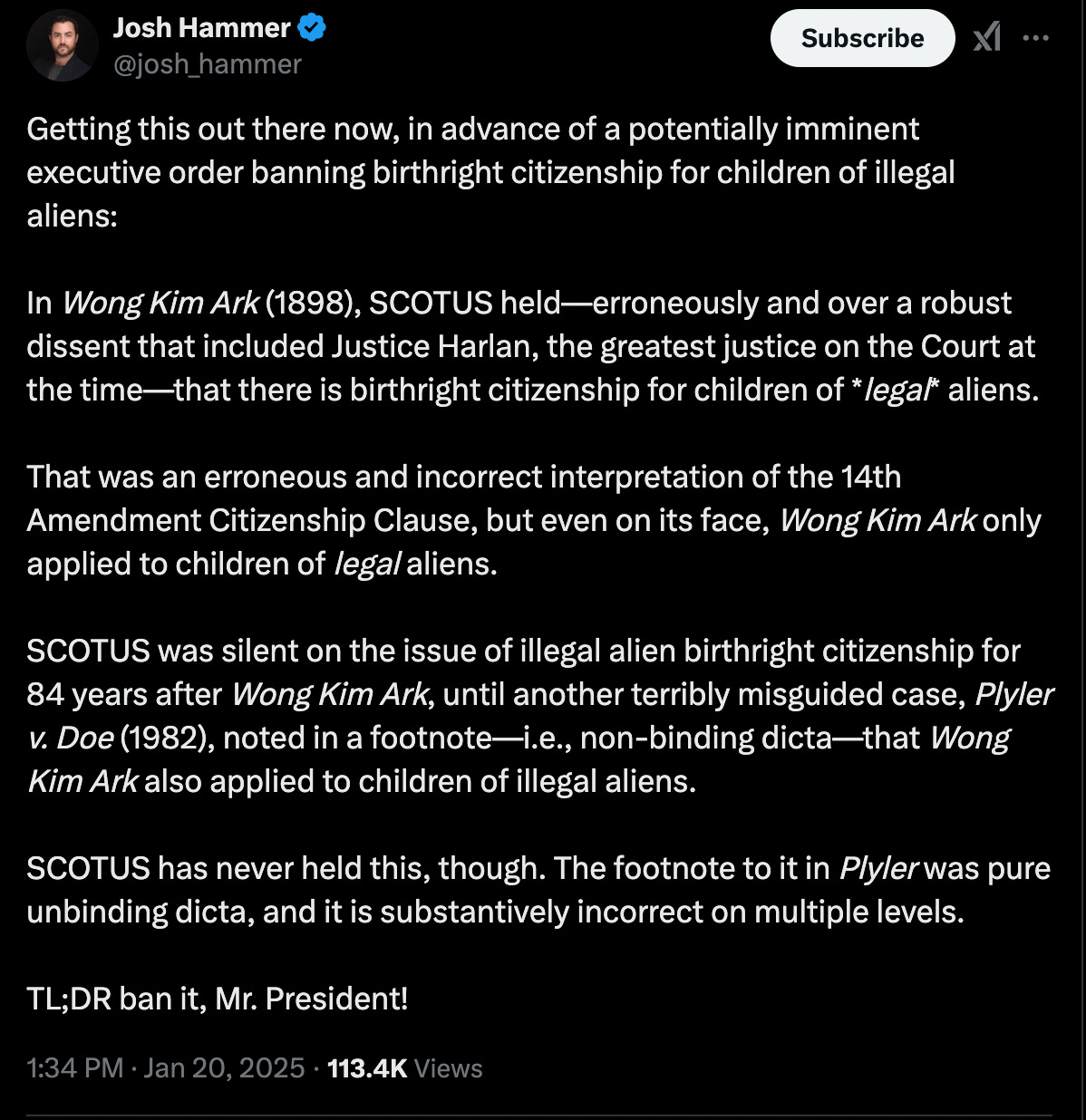

This is a pretty good tweet-level summary of the SCOTUS case law on this issue, but let’s go a little bit deeper. As you can see from this, however, the confident assertions that this is a settled matter of constitutional law are, at the very least, not telling the full truth.

The source of the assertion that birthright citizenship is in the Constitution comes from the 14th Amendment. The 14th Amendment arguably inaugurated an entirely new regime in the history of the United States, laying the groundwork for a complete alteration of the constitutional reality that existed before. What should be taken into account in this discourse is that those who argue for a more “conservative” reading of the 14th Amendment are trying to square it with what came before; the progressive readers of the 14th Amendment see it as the radical break it really is. We have a question of continuity or rupture.

That said, I don’t think that should necessarily determine the correct reading of the citizenship clause of the 14th Amendment, on which this whole question hinges.

Let’s look at the text of Section 1 of the 14th Amendment:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

We are primarily concerned with the first sentence. The rest of Section 1 contains the more radical language that alters the constitutional framework so greatly. The constitutional question before the SCOTUS will be: do you read the first sentence in light of the original intent of the founding era, or do you read it in light of the intent of the post-1865 regime?

From here, then, we will concern ourselves with the arguments for limiting the scope of the citizenship clause—that is, the arguments against birthright citizenship for legal and illegal aliens.

For a comprehensive legal overview, you might appreciate this article from the Texas Review of Law and Politics by Amy Swearer, arguing for an “originalist” interpretation of the citizenship clause.

For those with the time for long Youtube discussions, here is a panel with Michael Anton (who served in the first Trump administration and will serve in the incoming administration in the State Department), and Dr. Edward Erler.

Both of these men are legends, in their own right, in certain niche circles—perhaps not so niche for Anton these days. You have probably heard of Michael Anton, but you may be less familiar with professor Erler. Erler is a longtime associate of the Claremont Institute, himself a kind of institution in West Coast Straussian circles. I had the pleasure of learning from him at a fellowship one summer not so long ago. He has written extensively on Birthright Citizenship, among other things.

If you don’t have time to watch that full panel video, I commend to you the brief American Mind interview above. One of the key points Erler makes is that in the debates on the House Floor about the 14th Amendment, its author(s) argued that to be a citizen requires exclusive allegiance—that is, to be “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” requires not being a subject of another jurisdiction. They preferred not to use the language of “allegiance,” owing to the fact that they considered the common law understanding of allegiance and birthright citizenship to be a “feudal doctrine,” incompatible with the principle of consent, so central to the Declaration of Independence.

For a thorough academic discussion of the Wong Kim Ark case and why it was wrongly decided, laying the groundwork for the “birthright citizenship” policy we have today (or had, until yesterday’s executive order), I strongly recommend Chapter 3 of Dr. Erler’s book, “The United States in Crisis: Citizenship, Immigration, and The Nation State.” The blurb on the back of the copy I am holding in my hands reads:

”This is not just Ed’s definitive statement on the subject; it is THE definitive statement on the subject. Case closed.” - Michael Anton

I suspect that Dr. Erler’s case will be the one made by the administration in defense of its EO, so if you want to get ahead of the game, read up.